Treasure Hunting

OK Go, The Beatles and exploring the adjacent possible in the pursuit of greatness

At the end of summer there is this odd thing that happens in Corporate America where many people start to plan for the year ahead. Like kids making birthday wishlists a year in advance, or Starbucks making Pumpkin Spice Lattes in September, the annual planning season happens way sooner than one would expect. After those months of planning come the New Year everyone then takes their wishlists and starts to work towards these objectives.

It’s such a standard process it’s hard to think it could be otherwise but this is a collective delusion. For anyone aiming to create something new, planning can be a trap.

In “How to make living systems” I wrote about how our world is addicted to planning: the idea that instead of having a very clear, final outcome we should follow a generative processes where we will, purposefully, not understand the end-state, is anathema to most people. Not having a long-term plan is seen as a flaw instead of a feature of the generative system.

But there is an alternative to master planning.

“Why Greatness Cannot be Planned”

The manifesto against grand objectives is the book “Why Greatness Cannot be Planned: The Myth of the Objective” by Kenneth Stanley.1 I’d forgotten how much I loved this book until I picked it up again for this post. It’s one of those small little volumes that I have marked up in pen like a madman; it’s chockfull of wisdom.

The summary of the book is as follows: We have to give up the myth of objective-based planning as a fruitful path towards creating impactful new things. Having objectives is fine for incremental changes where you are "one stepping stone away" or for situations where you clearly understand the steps needed to get to your goal (e.g., “I want to plan dinner tonight” “I want to open a restaurant”) but having objectives is an anti-pattern for anything ambitious and novel (e.g., “I want to invent a new cuisine” “I want to be a great writer”).

The reason for this is that when you see how great new things happen, it’s not by someone setting out in advance to “achieve greatness” but rather by exploring and exploiting “adjacent possible” opportunities and then pursuing them to find something new. For example, to develop the computer in 1800 it would not have been helpful to say “we need to make a plan to develop a computer” since the set of innovations needed for a computer could not have been foreseen in advance. Similarly, much of what happens in typical planning is equally unhelpful and divorced from more specific next steps that could lead to new opportunities.

Here is Stanley with more:

Because most interesting inventions are simply the most recent fruits of chains of ideas spanning centuries, they too will necessarily depend upon a prior invention created for an entirely different purpose. In fact, stretching this line of thinking to its logical conclusion leads to a provocative hypothesis about invention in general: Almost no prerequisite to any major invention was invented with that invention in mind. While this idea sounds strange, if it's even partially true then its implications for objective-driven innovation are sobering. After all, what hope is there of achieving ambitious objectives if their prerequisites are almost sure to come from someone with an entirely different objective? But there is good reason to believe that the world works exactly in this way. Electricity was not discovered with computation in mind, or even with vacuum tubes in mind, and neither were vacuum tubes invented to foster building computers. We simply lack the foresight to comprehend what one discovery will later make possible.

To quote Niels Bohr, “Prediction is very difficult, especially if it's about the future!” It’s not helpful therefore to rely on what we imagine the paths towards greatness to be, since those paths are almost certainly wrong. Not only are grand plans flawed, they can also be harmful since when we are obsessed with these ideals we often overlook the smaller steps we can take to move us forward.

So what is the proposal instead of having grand plans and objectives?

Stanley’s recommendation is to embrace “novelty search”, moving into treasure hunter mode looking for adjacent possible stepping stones. The telltale sign for these opportunities is interestingness - we must be on the lookout for things that look interesting and explore them. Like someone walking across a lake from stone to stone, the opportunities can then add up to completely unexpected changes over time.

Here’s Stanley with an example:

You may not need to see a survey to be convinced that New Year's resolutions often don't stick, but just for the record, although over half of the people who make such resolutions think they'll succeed, only 12 % actually do.

That kind of dismal statistic is a reminder that setting objectives, while appealing in the moment, is the easy part. It doesn't take much effort to state what you want to be, where you want to go, or what you want to accomplish. The problem is getting there. More specifically, the problem is that it's hard to identify the stepping stones between here and the objective. This insight suggests a strange idea: Perhaps the effort invested in specifying clear objectives would be sometimes better spent in identifying promising stepping stones, but not specifically those leading to the objective. After all, the objective offers few clues to what its stepping stones should be. So maybe there's a different way to think about search. Instead of worrying about where we want to be, we could compare where we are now to where we have been. If we find ourselves somewhere genuinely novel, then this novel discovery may later prove a stepping stone to new frontiers. While we may not know what those frontiers are, the present stepping stone becomes the gateway to finding out.

OK Go’s “Upside Down & Inside Out” Video

A great example of this approach is OK Go. For those of you not familiar, OK Go is a band that makes incredible music video productions in time with their music. (Look at their YouTube channel for a good break.)

One of my favorite OK Go music videos is “Upside Down & Inside Out” where they film their entire song in zero gravity perfectly timed to the music.

The way they came up with the video is a great example of novelty search in action. In the documentary talking about how they made the video, they mention how they were approached by someone in Russia to offer them a zero-gravity plane for their video. They accepted the offer and flew to Moscow, however, the crew wasn’t ready for their approach. Here is the lead singer describing what happened:

“Normally what people do when they make a film is plan very carefully and then shoot. What we [did instead was say], “Get us into the airplane and once we’ve played for a week then we can tell you what the real idea is.”

The Moscow crew thought they were bonkers:

“We [the crew] were really looking forward to seeing the script. OK Go said there was no script but rather a leap of faith… We agreed not to agree how we were going to film this.”

OK Go continues:

“The crew I don’t think took us seriously at all. They figured a film crew would show up and know exactly what they want. We showed up and were like “You play with the rubber balls, I’ll play with the hats, and you do flips. OK? Then after this flight we’ll all get back together, see what went well, and we’ll try it again!”

So in the first week of flights, we did 6 flights and the [film] crew just sat there watching us like “What is the matter with these morons?” Because we were just literally bouncing off the walls and being silly.

I don’t think they took it very seriously because they didn’t think it was part of a real process.”

Once OK Go had a chance to regroup after the initial round of flights, they worked through the opportunities afforded by this film location (i.e., they worked through the adjacent possible) and then they clarified the details needed to make this music video.

The Beatles & “Get Back”

It’s minute 62 of the first episode of “Get Back” on Disney+. After days planning for their upcoming (and soon to be final) concert, the Beatles are back in the room trying to come up with their next album.

It’s morning and we see Paul approach Ringo and George. Paul sits down, grabs a pick, and starts messing around on the bass. He starts riffing. George yawns, still waking up. Ringo looks really bored.

Paul continues to riff. He plays chords. He hums and starts to move his leg as he lands on sounds he likes. He mutters nonsense… Until suddenly, out of the noise emerges the now world famous rhythm of the song “Get Back”. It’s a breakthrough!

But nobody cares. There is no earth-shaking realization. Nobody in the studio is excited. George keeps yawning…

After a few more minutes with nobody caring, suddenly Ringo starts to hear the tune. He starts to clap a bit and then we hear Paul sing “get back to where you once belong.” Out of the ether the chorus rises!

You can see the beginning in this YouTube video excerpt:

And you can see a few minute later here:

There’s now a hook. Pieces start to fall together. George starts to join in on the guitar. Paul starts to develop the verses. The chorus suddenly emerges from all three of them at the same time. Ringo starts to emerge from his comatose morning and sings the chorus. There is suddenly a beat and now we have a real song. Paul starts to really jam, then Ringo moves to the drums and before long, John arrives in a big fur coat, grabs a guitar and joins in.

Some time later, they work through the verses. As they flesh it out they find patterns in the song that connect to the news - they start to frame the song as a statement against white nationalism. We now have the song “Get Back”!

This entire song emerged. It was not planned. And this is not an exception. Great songs emerge in this way. If the Beatles had set out to make the song constrained to a desired goal from the outset, it wouldn’t have had that magic. Instead, by playing around in their collective musical latent space – jamming, riffing, exploring – the song emerges.

Building living systems through the generative process

This emergence without a plan is also how great living buildings & cities grow as well. I wrote more about this in “How to make living systems”:

The process used to generate a system is the key to making it full of life. It’s not the genius of an individual or group of people, it’s not one amazing diagram on a piece of paper with a brilliant “aha” moment - if we see something that is full of life, it’s because it followed a specific process. And this same process was used to generate all things we see full of life: from your body, to the flower outside your room, to a beautiful rug, to St. Mark’s Square in Venice, to Yosemite National Park, to the forest near your town.

Living things come from a generative process of development that strengthens life through gradual improvements made with an eye to strengthening the “wholeness” overall via the “fundamental properties.”

As Stewart Brand says in the book “How Buildings Learn” talking about Venice:

American planners always take inspiration from Europe’s great cities and such urban wonders as the Piazza San Marco in Venice, but they study the look, never the process. Garreu asked social historian Dennis Romano and planning historian Larry Gerkins about Venice.

Romano [writes,] “Those who now romanticize Venice collapse a thousand years of history. Venice is a monument to a dynamic process, not to great urban planning… […] Gerkins [writes,] “The Piazza San Marco was not planned by anyone… Each doge made an addition that respected the one that came before. That is the essence of good urban design - respect for what came before.”

Of course, planning can still be good when you have a clearer understanding of the steps required

Lest you think I’m just an “anti-planning radical”, I acknowledge there is a space for doing “great things” through incremental known steps. This works when you already know the stepping stones! The nuance is very important but is almost always lost...

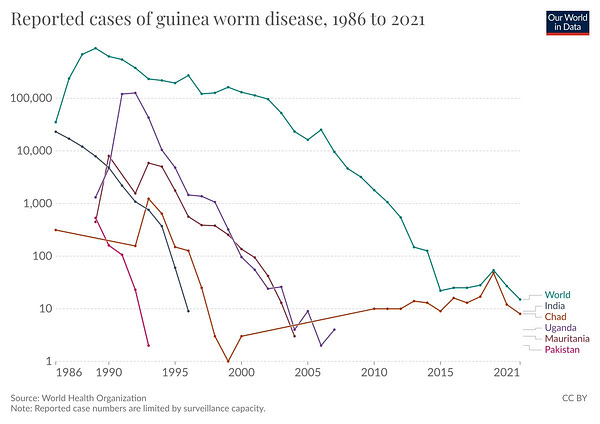

A great example of achieving great things through planning is eradicating the Guinea Worm around the world: there was a clear goal, a clear known cause, and by following clear steps it’s almost eradicated after a few decades. Here is Saloni with more:

The eradication campaign has made so much progress because we know how to reduce the transmission of disease. By preventing people from consuming contaminated water. There are many ways that this has been done.

providing water filters

treating water with larvicides to kill worm larvae

educating people on where to drink water safely

improving access to clean water sources”

This progress was possible due to the eradication campaign, which began in the 1980s.”

Living without objectives: following the way (道 / Tao / Dao)

In case it’s not clear, I feel very passionate about this topic. I think the main reason why is because I have seen the greatest minds of my generation driven mad by endless planning sessions (to paraphrase Allen Ginsberg in a way he probably never foresaw). The amount of hours I have spent creating plans that ended up being pointless would be shocking were it not so commonplace. And yet, even recognizing the collective time sink, it’s still taboo to be anti-planning. Of all my posts, this might be the most controversial.

On a personal level, moving beyond the grand objective frame of mind requires a willingness to be an explorer. One has to:

Learn how to become a “treasurer hunter” - feel your way through the adjacent possible and find areas that are interesting. Create the spaces to explore these adjacent possibles.

When you find these new interesting opportunities, try to harvest them and incubate them in your life - find the treasure, then try to expand its connections to other parts of your life.

Get comfortable not having a plan. Focus more on the stepping tones. Think in systems not goals; the stepping stones are the system.

So much of my youth I was driven mad by the fact that I did not have a specific destination in mind. Many people I knew had clear objectives for their careers (doctors, scientists, lawyers, actors) - I always just had interests but no clear goal. I always considered this a flaw but I now realize I was falling into the objective-mindset trap – being an “interestingness treasure hunter” was also a path worth pursuing. This comes much more naturally to me.

Follow the path; look for the way.

I’ll close with a quote from Stanley:

“Letting go of objectives is [difficult] because it means letting go of the idea that there is a right path. […] Instead of judging every activity for its potential to succeed, we should judge our projects for their potential to spawn more projects. If we really behave as treasure hunters and stepping stone collectors, then the only important thing about a stepping stone is that it leads to more stepping stones, period. [If] you’re wondering how to escape the myth of the objective, just do things because they are interesting.”

“We can reliably find something amazing. We just can’t say what that something is!”

If you’ve made it all the way down here and enjoyed this post, please consider sharing it or liking it by clicking the button below. It helps others find this post and lets me know it was valuable to you 💙

If this was forwarded to you, you can also subscribe below :) Happy treasure hunting!

This podcast with Patrick O’Shaughnessy and Kenneth Stanley is a great recap of the book.

I love this! Defines so much of how I try to live. I do think that it is interesting to think about what immunities to living this way exist as most people like to live with more control and predictability.