On Christopher Alexander’s "Nature of Order" - Part II - On centers & the “15 fundamental properties”

This post became part of a series on Christopher Alexander’s "Nature of Order".

On centers & the “15 fundamental properties” ← this post

How to make living systems On the Fundamental Process to Generate Living Systems

Brasilia: life amidst modernism // Finding life in the spaces in between

I wrote a few weeks ago about how I started reading Christopher Alexander’s "Nature of Order" - thousands of pages on philosophy about the fundamental nature of beauty and life in the universe. This is my second post on the book going into the real heart of the book: analyzing the world around us based on “centers.”

The main point of the first post (“Degrees of life”), is that “everything [in the world] has some degree of aliveness - not just living things but everything. From the way that a group of people are arranged, the relations between buildings, the empty spaces of a foyer, the light falling on a book, buildings, people, clothes, dishes, the way dishes are arranged - all of existence. Moreover, Alexander argues strongly that “this feeling is rather strongly shared by everyone.”

The next part of the book explores what exactly is it that is driving this difference in “degrees of life”? Why do certain places and things have more life than others? And how can this be broken down analytically?

Below is my summary. Before going into it though, let me just say that once I’ve internalized this way of viewing the world, I can’t unsee it. It changes how I view everything… So let’s get to it, let’s talk about “centers.”

Alexander’s main thesis is that some thing or places’ degrees of life is a function of its overall “wholeness” - effectively, how well do all the pieces & spaces tie together. Given that the world “wholeness” is confusing, he chooses the (only slightly less confusing) term “centers.”

Now “centers” aren’t necessarily the center - they are pieces and the spaces created by the pieces. To some degree everything discernable is a center (I’ll stop putting it in quotation marks). So for example, if you take a room, the windows are centers, the doors are centers, the table is a center, the ceiling is centers, etc. Those pieces also create their own centers: the window creates a center in the way the light then flows through it and where the shadows fall; the table creates another center in the space below it, to the sides, above it, and way it changes the flows through the room; a tree is a center and it also creates centers above and below it, etc.

Here is another description of what a center is from Dorian Taylor:

[A center is] roughly as an identity, a discernible region of space, a perceptible thing—that is, in contrast to a non-thing. What makes a center a center is that you can point to it, draw other people’s attention to it. A center need not have a hard boundary, but it has to be bounded in some way—it can’t trail off into infinity.

Centers are recursively large - the room itself is another center within a house; the house a center within the neighborhood... And centers can be recursively small: components of the window are all centers - the window sill, the panes of glass, the wood, the door handle, etc.

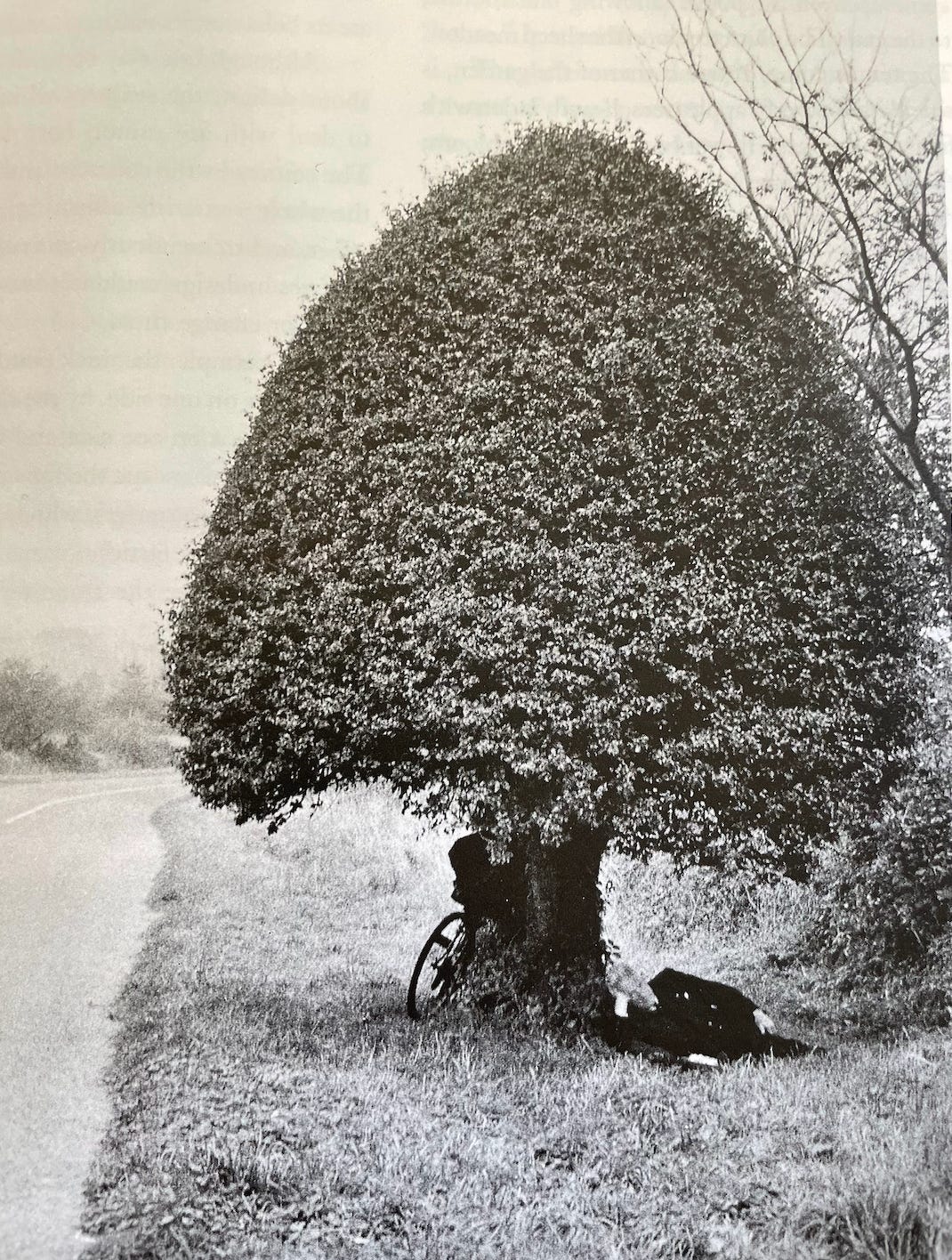

To give a concrete example, below is Alexander describing the centers in this photograph:

We see a tree, a road, and a bicycle parked at the edge of the road under the tree. In our normal way of looking at this scene, we see various fragments which seem to be "parts" of the whole: the tree, the road, the bike, the cyclist.

Learning to see the wholeness as it is in a case like this, not muddled or contaminated by words and concepts, is extremely difficult, but it is possible to learn, consciously, to pay attention to this wholeness. {…}

When we see wholeness as it is, we recognize that these seeming parts the road, the tree, the bike, these particular centers are merely arbitrary fragments which our minds have been directed to, because we happen to have words for them.

If we open our eyes wide, and look at the scene without cognitive prejudice, we see something quite different: a great swath of space, wider than the road, which tends to the distance and includes the flat land on either side of the road as one of the major centers in the scene […]. We see a space under the tree, between the road and the tree, as another obvious "place" or center within the scene. We see the spot where the person is leaning, on the right side of the tree, as a major point of concentration. Also, if we look carefully, we see a flat, ring-shaped swath of space under the tree, almost like a flat cylindrical donut, caused by the fact that the tree's foliage has been trimmed to just above head height all around. And we see the top of the tree, the wooly, bee hive shape of the tree itself-but it is not the tree which draws our attention as an entity-it is the top of the tree without the trunk-the mass of foliage. Thus the centers we see, when we look for wholeness, are not the centers which are captured by words, like "road," "bike," and "tree," but a different set of centers, which have no special words attached to them, and which are induced structurally by the overall configuration of this scene.

The wholeness of this scene is created by these centers, all of them together. They are really there, actually existing centers in the space. It is not our imagination, and not some great conceptual occurrence. Their existence and their strength becomes visible when we make our minds blank and look without focusing at major all parts of the page at once. In this unfocused or defocused state, we see the big swath of à the road space over grass and road, we see the cotton wool top of the tree, we see the trunk and the ring of space around it as the strongest things. The things which have easy names- the tree, the bike, the road (though they too have their relative degree of wholeness and centeredness) are less strong within the overall configuration. They are centers, too, but they are lesser centers within this configuration, and play a less important role within the structure as a whole.

For example, why does the rider of the bike put his bike under this tree? What invites him the is the donut of space under the tree, not the tree itself. Thus the wholeness and its real system of centers, hidden and not-hidden, are the structures which have impact on the world. We shall not understand how the world works unless we pay attention to the structure of wholeness as it is.

So that’s what centers are but they’re not all equal. Centers can be stronger or weaker AND centers interact with each other. So for example, having a window full of life in a room (i.e., a strong center) can make the rest of the room seem more alive (i.e., it can strengthen other centers).

Centers can be thought of as fields interacting with the other centers/fields around them. This is true at small levels (e.g., each tile in a pattern strengthens the other tiles) and larger levels (e.g., rooms full of life in a house can then make the overall house more full of life; a beautiful tree outside a house can strengthen the overall life of a house or street).

Now that we’ve covered what centers are, we can get to a core insight of “Nature of Order”: The more strong centers a given place/thing has, and the more they reinforce each other, the more life it has.

So going back to my previous post, if you have a thing / place (e.g., a street/parking lot/house/person/painting) that is more full of life than another, it’s because it has stronger centers and its centers more strongly reinforce each other.

This is the the new lens that has changed how I view the world: Everything is composed of centers and a thing or place’s degree of life is a function of how strong the centers are and how they reinforce each other.

After establishing this idea, Alexander then goes on at length to explain that he’s found 15 ways that centers can reinforce each other. Each of these patterns makes a center stronger.

I might have another post going into these 15 but this is already getting long so I won’t go into them too much. For now, here is the list (with more details at the link): (1) Levels of scale; (2) Strong centers; (3) Boundaries; (4) Alternating repetition; (5) Positive space; (6) Good shape; (7) Local symmetries; (8) Deep interlock and ambiguity; (9) Contrast; (10) Gradients; (11) Roughness; (12) Echoes; (13) The void; (14) Simplicity and inner calm; (15) Not-separateness.

It’s a lot to go through them but here is an example from Alexander describing how the strengthening properties come together with centers in a birthday party (words in capital letters are the “fundamental properties”):

Consider, for example, a child's birthday party and the high point of the party, the moment when the cake is brought in with the candles lit, and placed in the middle of the table. The table itself is LOCALLY SYMMETRICAL with a BOUNDARY and a STRONG CENTER. To make the boundary more solid, we put the place settings around the edge, each one itself destined to be a center. And to mark the main center, we place there a great jug of flowers, or the cake itself, making a GRADIENT toward the middle. And then, at each place set ting, we put a small place mat, with the knives and forks arranged around it in symmetries to create the center more firmly, and to create detail at the boundary of this smaller center. To make the place even nicer, we will perhaps use a lace table mat, which itself has a major center and a lacy, imbricated edge, again making still smaller centers around the center.

The big jug of flowers that fills the center of the table might perhaps have two candles, one on either side, to mark it and to form its edges. The minor center, the birthday cake itself, is also dec orated with a ring of small birthday candles in ALTERNATING REPETITION, marking its boundary, forming a chain of centers, leaving the central space in the middle of the cake empty (THE VOID) for the name of the person, or an ornament.

I’ve gone through a lot and probably lost most of you, so let me take a quick step back: why does this matter?

Centers & the fundamental properties that strengthen them explain how to make everything more full of life. It’s an analytical path to make the world more alive and it’s the only real explanation I’ve seen for how to analyze the world in this way. While you can find other works on wabi sabi and other descriptions of aesthetic patterns that are pleasing, they aren’t as prescriptive. This makes them hard to fully deconstruct and in turn, it’s difficult to construct the world around us in a way that is more alive.

Alexander’s approach provides the guide that lets us really look at the world around us and find clear paths to make it better. It helps us answer questions like, why does a window have the frame it has? What type of table would make this room better? Why do paintings have frames in museums? How is it best to organize a room? A house? A garden? A city? Why do suburbs often feel so dead? Why does Florence and other older European cities feel so alive? Why does this particular cafe “work”? Why does that other one not? Why does this new airport feel soulless even though it’s brand new and really expensive? Why is nobody sitting on the benches in this park? Why does this part of this town feel so much better than that other one?

I have a lot more to write about this but for today, I’ll leave it here.

We have the ability to make the world more alive. This is the way.