“This place is so wonderful.”

This sense of wonder – that a place can really radiate peace, aliveness, and energy – is something everyone can feel when they go somewhere special. You can feel it in the quiet beauty of Kyoto’s temples. The Golden Gate Bridge. A hillside town in Tuscany. There are places that people travel across the world just to visit, just to feel and experience their energy.

People naturally gravitate towards these places and it’s my belief that the world would be better with more of this energy. The feeling these places radiate makes the world richer and they make people feel alive and yet, unlike an ocean or a waterfall that is naturally full of life, these places are human creations.

We humans do not always make living things in fact, much of what we build can be ugly, brutish and lacking life. Creating the places that radiate aliveness requires an appreciation for how the aliveness comes to be and a sensitivity towards it. For us to nurture aliveness we need to understand the ingredients that sustain it.

This concept of how to make the world more alive is one that is investigated in depth by Christopher Alexander (a famous 20th century architectural philosopher from the West Coast). Over the past few years I’ve been enamored by his ideas and I’ve written about him in a number of posts (e.g., this post on Torii ⛩️). However, I want to explore this much further in this newsletter since I think about this concept basically every day.

What I want to do with the following series of posts is explore these ideas primarily through the lens of “interlinking.” For this post I want to provide an intuitive sense for what I’m talking about when I use this word and what I mean when I refer to “containerization” - a complimentary and often opposite force.

Before that, for those that are newer here, here is my quick recap of Alexander’s theories since they are the foundation.

VERY QUICK RECAP OF ALIVENESS

Everything in the world has some degree of aliveness - not just living things but everything. From the way that a group of people are arranged, the space between buildings, the way chairs are arranged in a lobby, the light falling on a book - all of existence. This feeling is rather strongly shared by everyone if they tap into it (e.g., everyone agrees intuitively that a parking lot is less full of life than the Golden Gate Bridge). That difference in feeling is a different “degree of aliveness.”

If you imagine everything in the world as having some degree of aliveness that it radiates, the more those fields shine and complement each other, the more the whole comes to life. This is “interlinking.”

The process to strengthen interlinking happens over time. One big reason for this is that planning for all the interlinking is impossible to know in advance so the way we improve things is by taking the current state and making it better vs. trying to plan too far into the future. (I elaborate on this in: “How to make living systems”).

Since interlinking is at the root of it all, let’s dive in.

AN INTUITIVE SENSE FOR INTERLINKING

To start, I want to provide an intuitive sense for what “interlinking” looks and feels like. Let’s take these two places below:

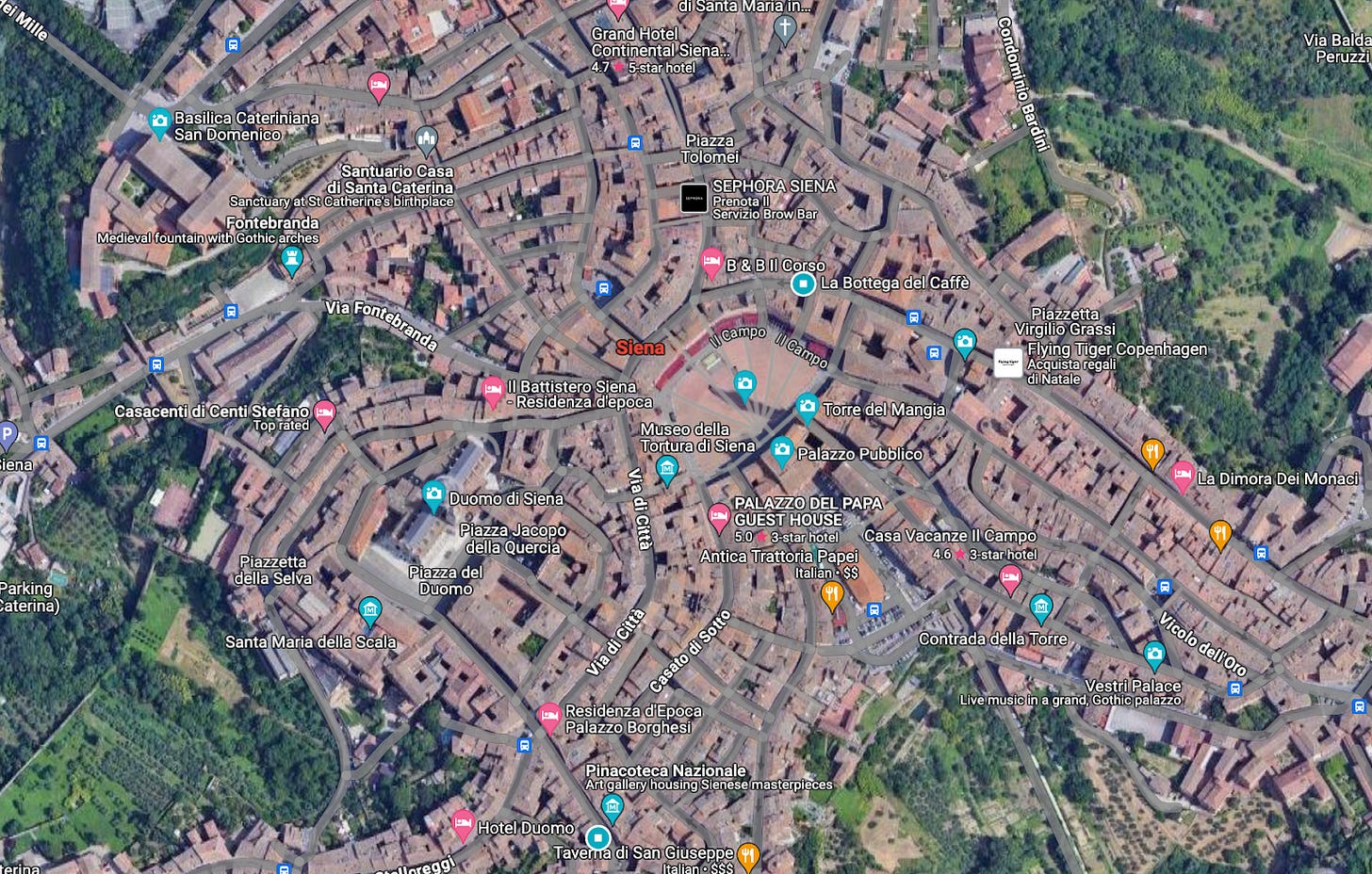

A random American housing development and compare it with Sienna in Italy

I think it’s pretty evident that the first set of houses is much less interlinked than the second. Each house in this suburb is almost like a container that does not impact or influence the ones surrounding it while in Sienna, the streets and buildings all weave together - each piece bleeds into the others making it much more difficult to say where discrete parts of the city start and end. In other words, the suburbs are much more containerized and Sienna is more interlinked.

Note however, that the suburbs don’t have “zero interlinking”; if you are in one of these houses you are always somewhat affected by your surroundings: Your neighbors might pass by sometime, you share some of the roads and services. Nothing is fully an island (even an island!), but in an American suburb it can get pretty darn close.

As for Sienna, it is highly interlinked but it’s not the only way a town can be connected. Take for example this beautiful town in Germany (Gengenbach, Baden-Württemberg). Here is a snapshot from a random spot on the map where you can feel the energy:

Seen from the sky, you can also see that it much more interlinked than a suburb. Note however that it’s interlinked differently than a medieval town: there are central bridges, open spaces near the river and a central river plays a big role.

Now, comparing picturesque quasi-UNESCO towns with a suburban housing development might feel unfair, so let me give you another example of interlinking vs. containerization in a different context.

Let’s take Wells Fargo.

Here is a Wells Fargo Bank that I passed in New Braunfels, Texas.

And here is a Wells Fargo Bank I found on the map for Union City, New Jersey.

The Texas Wells Fargo is much more containerized and less interlinked than the latter: The top bank is very removed from all the other buildings around it. It’s made for cars to drive through and it does not contribute much to the aliveness of its surroundings. While it could drive some behavior to the broader part of the town, most of the concrete that surrounds it is devoid of life, and any aliveness the building has doesn’t really extend to adjacent buildings (e.g., the Walgreens off camera is similarly containerized).

In the second photograph the bank from New Jersey is much more interlinked to the area it resides in: the buildings around it are impacted by what the bank does, how it looks, and how it operates; the shade from the buidling impacts and is impacted by other structures. For example the 7-11 across the street from it has a physical relationship with the bank and they feed off each other's actions and aesthetics. They also drive and share behavior: people might come to the 7-11 and then walk to the bank (or vice-versa). The crosswalk between them makes pedestrian access plausible and strengthens these patterns. Both of these places have generally weak centers (i.e., they aren’t that full of life) but on a relative basis you can see the interlinking at play.

Let’s take another example that isn’t housing. Here is a souk market in Morocco:

And here is a photograph of a mall in Brasilia

They both have some interlinking but you can see that the mall is much more containerized - while the mall as a whole benefits from having all of the stores next to each other (there is still much higher interlinking than say, the Wells Fargo in Texas), each store does not interlink with the others to the same degree as the souk where each stand’s goods merge into one large whole.

To clarify before I wrap up, my view isn’t simply “interlinking good - container bad” - it’s more subtle than this. There are strong benefits to containerization and not all interlinking is positive. My goal here is to point out that this overarching characteristic of interlinking is something that exists and changes how we perceive and feel these spaces as humans.

Interlinking is a dynamic that arises naturally from interactions between anything that exists. The more I look around, the more I see this dynamic at play. Managing the right level of interlinking to allow spaces to complement each other without overwhelming or destroying each other is the art we must relearn.

Interlinking is almost like universal glue and it’s a glue that can make things full of life when applied the right way. However in the last century – and especially since the advent of the car – the way we humans build the world around us has moved much towards containerization. We’ve done so to such a degree that the costs of containerizing have far outweighed its benefits… I’ll write about this more in my next post.

Until next time 🙏🏼