All is alchemy

Great things are made from simple steps

This week I wanted to write about a thought that keeps coming back to me almost like a mantra: “everything is alchemy.”

One definition of alchemy was the pre-chemistry concept for “the transmutation of ‘base metals’ (e.g., lead) into ‘noble metals’ (e.g., gold).” In this post, I’m not actually talking about making physical gold but instead metaphorical gold: the alchemical process of turning “base” things into “noble” things.

There’s a popular joke about how to draw an owl in three steps:“Step 1. Draw a circle. Step 2: Draw another circle. Step 3. Draw the fucking owl.”

For many that have tried following “how to draw” books, this joke probably sounds familiar: you have a few simple instructions to follow but they seem to omit a lot of missing steps. One reason I think this often happens is because the jump from small scribbles to complete owl feels like alchemy: impressive things are made out of lots of smaller steps and the transmutation that leads to greatness often doesn’t match the steps that precede it.

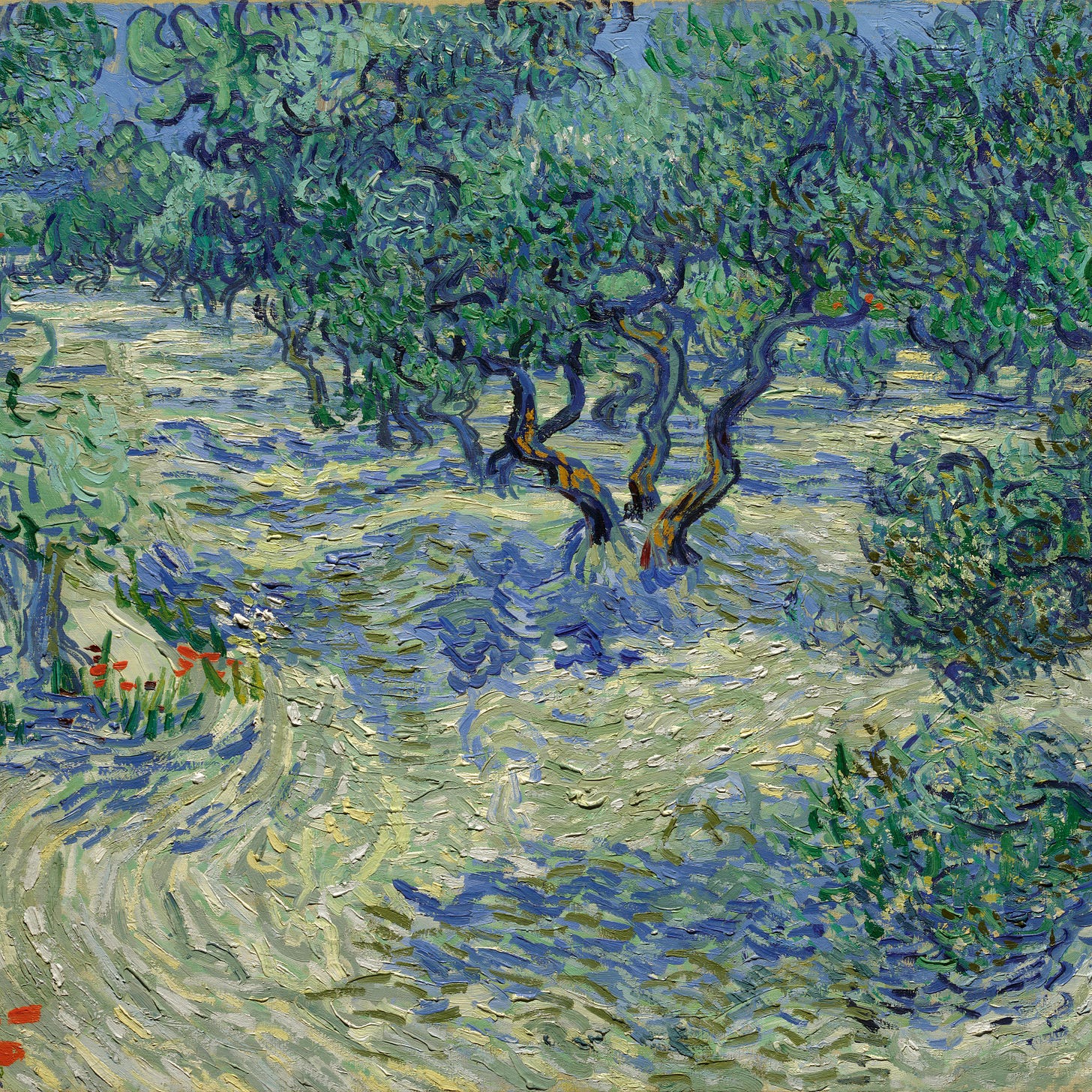

For example, a beautiful painting is an enormity of brush strokes on canvas. The brush-strokes themselves are actually not that complicated. “Anyone can do that” people will mutter, and often they are right. Many people could do that. The difficulty is having the patience to generate and then execute the time-earned skills to create the image from the simple components. The gestalt of the painting emerges from the details.

Magician “Load up”

In this vein, I was reading a book by magician David Kwong recently that captured the enormous amounts of preparation work that is required to execute a magic trick. I never had really considered that magic tricks are the result of absolutely extraordinary levels of non-magical, prep work:

Called "loading up," [the process] involves the advance or organization and placement of devices that will later be used to create a magical effect. Illusionists, close-up magicians in particular, might load up by running strings up and down their coat sleeves, or stuffing their pockets with gimmicked coins, extra cards, or maybe a fake thumb or sixth finger. Whatever equipment is called for, it will be loaded precisely so that it can be accessed and deployed the instant it's needed, but without the audience's knowledge-inside the gap, so to speak, between what they can see and what they will perceive. What they'll perceive, of course, is the seemingly spontaneous effect: the payoff of all these preparations.

[…[ What distinguishes an illusionist's approach to preparation are the extreme lengths to which he or she will go to ensure a desired outcome. Master illusionist David Copperfield, for example, is known to take two years to develop a piece that requires only minutes to perform, and especially complicated tricks can take even longer. One of his most famous acts, "Flying," in which he soared around the stage, passing through hoops and a Plexiglas box, took him seven years to perfect.

Let me repeat that: for one act, magician David Copperfield spent 7 years preparing! That is astounding… In another example Kwong provides, a magician memorized 15,000 things to make a particular trick seem like magic.

These are just an extreme example of what is true across disciplines.

Gestalt: more than the sum of the parts

I was recently trying to improve my watercoloring skills and I got to the point where I could do various strokes pretty well. I then attempted to execute a more impressive painting and realized I would have to make thousands upon thousands of those strokes, for dozens of hours, and combining them in a way that required years of know-how. Each particular piece wouldn’t be difficult but the patience to acquire the skill and then execute it, was enormous.

Cooking is the same. Making a masterful cake is a result of a large number of small, relatively simple steps. Each step does not look like a full cake at all and each step is relatively simple (measuring out eggs, flour, salt, mixing, etc.). The difficulty is in being able to stick with years of skill development and execute each step with high-skill. There’s a reason restaurants will often willingly give up their recipes and that’s because most of their magic comes from the execution.

There’s a story in Jiro Dreams of Sushi about how the apprentices that want to become chefs at this world-class restaurant spend years of their lives focused just on making rice. It sounds surprising at first but I think the reason why this happens is this one exercise is actually the foundation of a master. Perfecting this foundational step in the sushi-making process, is one of the many “basics” that need to be executed to create one of the best restaurants in the world.

This pattern extends everywhere I look:

Exercise: each rep is simple, the challenge is the consistency and improved execution.

Yoga: the positions are not that complicated - the challenge is having patience for the consistency required to go deeper into the poses.

Playing piano: you sit down and then play the keys. Of course there are better and worse ways of practicing, but ultimately it’s a lot of small, repetitive tasks that add up to the competency of “playing the piano.”

Writing: In Anne Lamott’s book Bird by Bird, she recounts how her older brother once was struggling to write a report on birds and didn’t know how to start. Lamott’s father told him: “Bird by bird, buddy. Just take it bird by bird."

Gardening: getting soil, planting a seed, fertilizing, watering - no step is too complicated. The results when combined over long-periods of time, however, are magic.

Focusing on the inputs & developing patience

The first corollary to everything being alchemy is that you should beware the trap of role-playing the dream instead of focusing on the work required. I mentioned some of this in “How to make living systems,” but often we fall into the trap of wanting the outcome and ignoring the process that leads there. A simple example would be people that say “I want to be in shape” and overly focus on the dream instead of “I want to do X minutes of exercise every day.” Focusing on the smaller components and the process that will lead to the outcome provides a better path. Sometimes people refer to this as “focus on the system, not the goal” which I think gets to the same idea: identify the sub-components of the thing you’re trying to do and get better at those.

Here is an example on this from a recent study that was able to improve kids school grades by focusing on the inputs (homework/attendance) vs. the outputs (higher grades themselves). Paying the kids to focus on inputs improved their grades. Meanwhile, “[the] irony is if you pay for test scores, you get nothing.”

The second corollary to alchemy is that to do anything meaningful requires a lot of patience. Going back to the magician examples, having an amazing magic trick takes them years; Jiro’s chefs practice for a long time just on rice; artists develop their skills over a lifetime. Mastery takes time - patience is the scarcest resource.

This is one reason I love Zen. As I wrote in Monotasking, mindfulness enables you to see the drudgery of maintenance as something beautiful. If you’re able to have this mindset, everything is brighter: the gardener tending the garden is focused on the joy of nature; cleaning dishes is respecting the tools that made the meal; repeating a yoga pose is being grateful for your body. Mindfulness helps you not get lost in the future dream but see the beauty today.

The gestalt of great things comes from the simple. The missing piece is almost always the patience to continue the small, repetitive pieces required for mastery. Find beauty in the craft.

PS - I will be sending the newsletter more sporadically as the summer unfolds. We’ll see where the thoughts flow… Happy July!

Really liked this piece, revisited it a couple of times. Reminds me of the Teller quote "sometimes magic is just someone spending more time on something than anyone else might reasonably expect."